How the Stomacher® came to be by

Dr. Anthony N. Sharpe

At the start of the 1970’s, after moving into the Microbiology Division of Unilever Ltd’s Colworth House Research Laboratory (Bedfordshire, UK), I was tasked with improving efficiency in the 25 or so food microbiology labs in Unilever’s food manufacturing plants.

Processing techniques for the mass production of food products were less safe than traditional home cooking, and this was becoming more prevalent. The new food products were designed to “up sell” simple raw ingredients in more profitable forms, such as recipe dishes, ready meals, and snack products. In addition, the way the raw ingredients were grown or raised was also starting to present new problems for food hygiene. It was the start of mass food microbiology testing, from “farm to fork” and the existing sample preparation technology just could not keep up with the growing demand.

Suspending contaminants in diluent is usually the first step in a food microbiological analysis. Two minutes of blending (e.g., of 10g of food in 90 mL diluent), regardless of food type, had been widely used for many years, presumably based on some study of comparative recoveries. A time and motion study by my technician Adrian Jackson and I showed that operations to do with this ubiquitous step were a prime target for improvement. Most UK Labs used “Ato-Mix” bladed blenders, European ones the UltraTurrax turret blenders, and USA labs used Warings and Osterizers (similar to Ato-Mix).

We found that bladed blenders took up over 30 percent of the total laboratory analysis time, from the customary 2 minutes blending, cleaning and re-sterilizing, servicing bearings and in collecting and moving blenders to and from the prep room. The time and motion study also showed us that for a blender with bearings in less-than-perfect condition, the temperature of a suspension could rise as high as 60ºC. This revelation made me wonder how many samples had been pasteurised before they had even been analysed over the years.

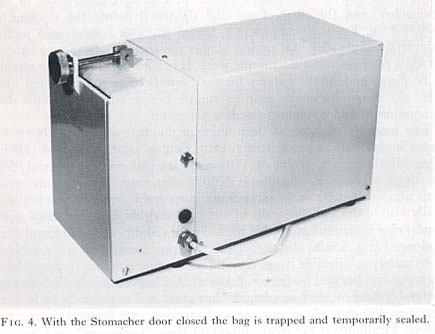

Finding a way to avoid the need to sterilize anything after liberating microbes into suspension was our target – and we considered various sterile containers for “doing something” to a sample in a diluent. Plastic bags were an obvious choice, but what one might do in a plastic bag seemed no match for the ferocious process inside a bladed blender. We thumped filled bags on a bench with our hands, but it didn’t look promising. The “bag idea” might well have died, were it not for serendipity.

As an unabashed packrat, I had saved all sorts of equipment discarded from other labs, one item being an artificial-lung machine from the Biology Division next door.

With a “why not just try it?” and some Meccano®, we converted that artificial lung into the first Stomacher® in an afternoon. The microbiology astounded us. Total aerobe counts were as high as from a blender, suspensions were clean and easy to pipet, and the temperature rise was essentially zero. Eureka!